There’s no denying that there is a gender imbalance when it comes to engineering. In the UK, only 12 per cent of engineers are female. A quick Google search on the matter will bring up countless articles busting myths about STEM subjects being a man’s domain (even though female students often outperform their male classmates in these subjects). More often than not, such reports point at a seemingly endless number of barriers presented to women who would otherwise become engineers — a lack of role models, sexism in the workplace, a concern over progression prospects.

Of course, these are all valid obstacles. But there’s a greater issue impacting British engineering in general, and a lack of female engineers is a symptom of a greater problem within the sector. After all, if it were simply a case of engineering in general throwing up obstacles for women, why does Spain have a relatively even number of male and female engineers?

What if it’s not simply a case of engineering shutting its doors on a pool of potential talent?

What if people — men and women alike — just aren’t knocking at the door of British engineering?

No question of ability, but of desirability

When it comes to addressing the lack of female engineers, often we will hear phrases such as “it’s because girls are brought up to believe they can’t do maths!” or “it’s because we treat engineering as a ‘man’s job’”.

This might have been true many decades ago, but in the modern day, it’s been quite some time since such strong gender biases were in play at an educational level. There is still work to be done, of course, but the idea of an entire sector being cordoned off as “careers for men” and “careers for women” has long since been kicked to the curb. Indeed, our female students are under no illusions — engineering is, as far as they are concerned, as valid an option for them as it is for their male classmates.

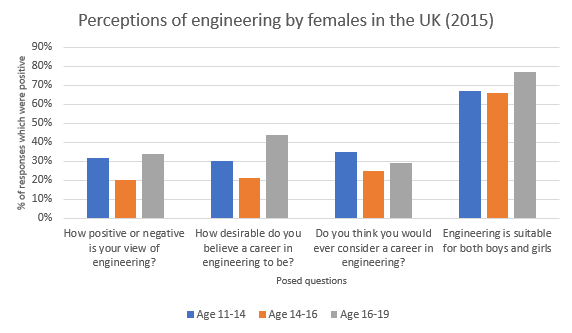

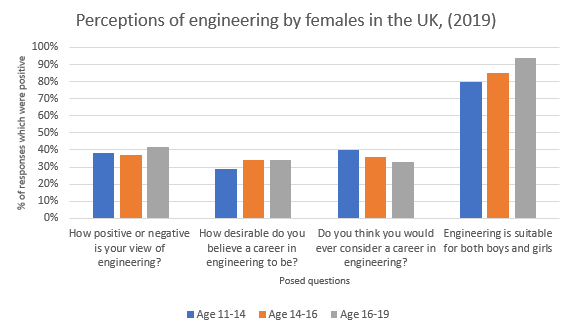

Research by EngineeringUK highlighted this perception from 2015 to 2019:

As the graphs above show, girls do not believe engineering is “just for boys”. In fact, the perception is only increasing, with 94% of girls at school leaving age (16–19) in 2019 saying they agreed that engineering is suitable for boys and girls. 81% of boys at school leaving age in 2019 agreed too.

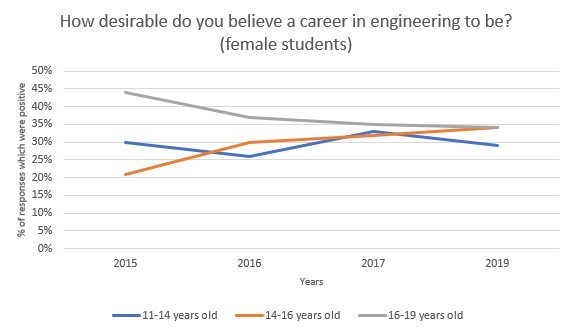

It’s not that girls don’t think they can be engineers, then. A perception of ability is not the problem. A perception of engineering as a desirable career, however, is certainly in play.

And it’s getting worse.

The perception of engineering as a desirable career path is dropping among 11-14 year old girls and 16-19 year old girls in particular. This could be cited as proof that more needs to be done to break down barriers and build up role models for potential female engineers in order to make the career path look more attainable and aspirational for women.

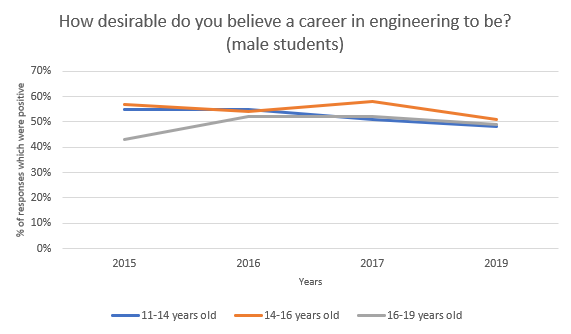

However, it’s important to note that boys are not much more enthralled by the idea of becoming engineers either, with a slight decrease also present in the last four years.

There is certainly a case to be made for the damaging effects of gender stereotypes, but clearly, girls are confident that they are equally capable to pursue engineering as a career — if they wanted to. EngineeringUK surmised that: “Barriers to pursuing STEM education and engineering careers — those relating to a lack of knowledge of engineering, for example — may be common to both genders and point to the importance of stepping up engagement with all young people.”

Engineering in the UK, it seems, is simply not showcasing itself as a desirable career path to either genders, and the impact of this is simply showing more in a lack of female engineers due to the residual remnants of gendered stereotypes amplifying the overall problem.

But why is engineering not appealing to men or women?

Engineering is appealing — the UK is selling it short

As previously mentioned, this is not a global problem. The UK ranks as the lowest in Europe when it comes to female representation in its engineering workforce.

According to civil engineer Jessica Green, the issue is certainly on a national scale. In the UK, engineering simply isn’t presented with any of the glamour or prestige that parallel occupations, such as architecture, is afforded. In fact, Green admits she herself “turned [her] nose up at engineering”, believing that to go down that route would mean spending her career “dressed in overalls working in tunnels”.

That, she points out, is the concept of engineering that the UK pushes out. Despite the years of academic study and on-the-job training that many engineering roles require, for some reason, engineering is denied its rightful sense of achievement and prestige.

Meanwhile, as Green points out, being able to call yourself an engineer in Spain is certainly held in high regard. One cannot call themselves an engineer at all without going through a difficult six-year university process, after which the title of “engineer” is awarded. It is held in the same regard as becoming a doctor. It’s little wonder then that Spain enjoys a relatively even number of male and female engineers.

Meanwhile, in the UK, the word “engineer” is used far more loosely. Not only that, but there’s a sense of ambiguity in the UK regarding what an engineer is. A lack of representation compared to other prestigious roles, such as doctors or lawyers, means that many people simply think of overalls and hard hats when it comes to engineers — despite the fact that plenty of engineers work in office environments or in a digital field.

The solution: establish the prestige

It is clear that engineering as a whole needs to rebrand itself in the UK, and not just for women. Female students in the UK are perfectly confident in their ability to become engineers — instead of a feeling that they need to prove themselves to the engineering sector, it is in fact the engineering sector that needs to prove itself to potential employees.

Diane Boon, Director of Commercial Operations at structural steelwork company Cleveland Bridge, states: “To be a woman in engineering — as with everything in life — you need to work hard. But so do the men. Being a woman has neither helped nor hindered my career in this incredible field. What engineering needs to do smarter is raise its profile, make itself more appealing to future generations — it needs to reposition itself.”

By building up the prestige of engineering and holding it in the same high regard as our European neighbours, the UK engineering workforce would no doubt begin to see a much stronger and swifter change in terms of gender representation within engineering.